It’d been several years since I ventured this far offshore, so this journey was a welcomed one. Teamed up with Dr. Brad Seibal and his science party aboard the R/V Endeavor, we set out about 200 nautical miles south from Rhode Island, which put us off the Maryland/Delaware coast, out into the Gulf Stream. The 20 hour steam offshore was uneventful – just full of focus by the science party as they prepped for the intensive weeks of work ahead. We fought some large swells which made for our first 48 hours adjusting to life at sea all the more difficult. The first night, I did all I could to not get tossed from my bunk.

It’d been several years since I ventured this far offshore, so this journey was a welcomed one. Teamed up with Dr. Brad Seibal and his science party aboard the R/V Endeavor, we set out about 200 nautical miles south from Rhode Island, which put us off the Maryland/Delaware coast, out into the Gulf Stream. The 20 hour steam offshore was uneventful – just full of focus by the science party as they prepped for the intensive weeks of work ahead. We fought some large swells which made for our first 48 hours adjusting to life at sea all the more difficult. The first night, I did all I could to not get tossed from my bunk.

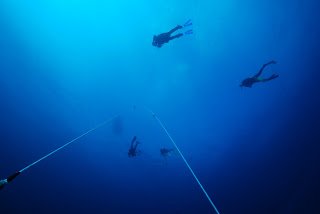

The dive operations required bluewater diving – our research site was over some 10,000 feet of water, so needless to say there was no bottom or hard structure to use in guiding our dives. However, that does not mean that there was nothing to see. Out in the open ocean, we experience the true three dimensional space that covers the vast majority of our planet. Within it, huge communities of pelagic critters – ranging from huge to microscopic – thrive. Many never see land, nor the seafloor, and many more never see the light of day. Within this blue vastness there is a ‘structure’ however. Temperature, light, salinity, nutrient levels, and other measurable parameters define the open ocean leaving layers upon layers, upon layers to be explored – along with each’s inhabitants. In this blue vastness, the aliens of the sea – squids and jellies – are abundant. They are remarkable in their ability to live in a three dimensional world.

At night, the creatures from the deep will ascend to areas that are now at lower light levels to feed. Needless to say, night diving ops were undertaken to observe these less commonly seen creatures. Night diving in the middle of the ocean is ominous and intimidating. The only frame of reference is the downline and the small microcosm created by your dive light which basically illuminates your immediate viewing area. Colored cyalume sticks are used to mark each diver, and the downline on the bluewater rig. Communicating at night is difficult. Staying at a reasonable distance while bluewater diving is important so as to not entangle one another’s tethers. Light signals are used to the extent possible to indicate an ‘OK’, with the safety diver managing depth and time limits. Occasionally shutting off your dive lights leaves you in anything but a pitch black void – as bioluminescent critters glow when agitated by our swimming through the water.

The cruise worked nearly around the clock, taking advantage of weather and variable conditions at the study sites. We worked from the Delaware coast over and up to Hydrographer Canyon, and then Oceanographer Canyon, where we concluded the fieldwork.

Diving in the middle of the ocean, off the margin of the continental shelf at night brings you a step closer to home – you realize just how infinitely small you are in this Blue Planet, and there is an ocean of opportunity out there right at your fingertips. After this two week journey, I am convinced that bluewater offers much in evolving diving and exploration practices to advance science, and also examine how we humans may better intervene and exploit this vast unutilized space here on Earth.